How to avoid knee pain in TAI CHI

Preventing Knee Pain in Tai Chi: Small Changes to Save Yourself and Your Knees

Tai Chi is a gentle form of exercise that can help improve balance and flexibility, but it can also cause knee pain if not done correctly.

Written by Paul Read (teapotmonk)

Prefer to listen?

A generated discussion on the report can be listen to here for those that prefer to spend some time away from the screen. (Download option available)

History of Knee problems in Tai Chi

A Survey of over 200 Tai Chi teachers* in the early 1990s revealed that over 61% of all teachers reported Tai Chi practice led to some form of knee injury, to either themselves or their students.

As it is not unheard for students to quit Tai Chi without telling instructors why, we can only ponder over whether one of these reasons could be knee pain experienced in the class. This is particularly true if a new student has come to Tai Chi believing that such a gentle practice can only be beneficial, irrespective of how it is taught.

We are now aware that high impact sports can damage joints, but do we know enough about low impact exercises like Tai Chi? And is it possible that they could do more harm than good?

Traditional Teaching Methods Can Be Harmful

Historically, Tai Chi was taught orally. Instruction was given by encouraging students to watch and copy. Questioning and doubting procedure or technique was frowned upon and discouraged. Some teachers still follow these traditional lines, claiming that by doing so it is more "authentic". This is true, but authenticity is not something you can inherit. it must be earned, and by itself, doesn't confer safety.

Consequently, such unquestioned practices became the norm, as outside studies on physiology and structural mechanics are seen as unrelated or irrelevant. Tai Chi, like many eastern disciplines, is seen as something almost akin to magic, or a mystical martial art shrouded in monastic secrets. What relevance has science and physiology for such esoteric practices?

But as 21st century practitioners, we cannot defer to such delusions. It is upon us all to read and learn as much as possible and to make our practices as safe as possible. This article is by no means a definitive account of knee misuse in Tai Chi. Others will have better knowledge than I. So keep reading, and keep learning. And share what you know so that others can contribute to this topic.

Bad Knee Practice in Tai Chi

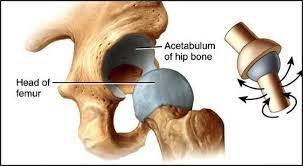

In crude terms, the knee is a hinge joint. This means that its safe range of motion is limited to a forward and backward motion. Why is this important? Well, it is important because we are often told to perform actions that assume the knee is a ball and socket joint - like the joint in the hip or the shoulder. These joints are capable of rotation, but not the knee.

In Tai Chi Forms, as we move slowly from one posture to another, we are told to either remove the weight from one leg, or keep it in the leg. It is at this moment that we need to pay special attention for if we are told to keep it in the leg and change direction, and keep the weight bearing foot flat on the ground, then this twisting pressure on the knee joint can lead to pain, soreness or even ligament damage. These moves do not strengthen the knee, they weaken it.

There are many examples in the Tai Chi form, such as the turning kicks or when shifting weight from one forward leaning stance - such as Shoulder Stroke or Ward-off Left - that engages the joint in this way. Here, the weight of the leg remains in the front leg whilst a turn in direction is made. Without realigning the foot first, this turn places stress across the knee and forces it into a twisting position whilst it bears the weight of the body. For advanced students, this can be done safely by timing the weight change and posture shift precisely with the foot rotation, but for most new students this is challenging manoeuvre.

Far more sensible is to remove the weight from the leg first, then turn the empty foot using the waist and hips, then return the weight safely into the leg (not unlike the process employed in the Single Whip move in which weight is quickly shifted from one leg to another in order to turn the hips safely 180 degrees). So you see we have a precedent in the form, we only need to apply it throughout.

There are plenty of examples in the Tai Chi form like this that require the attention of teachers when shifting weight and changing direction. It is important that all teachers explore these moves. If we do not, then we will be perpetrating the same errors that previous generations have made - ignoring the knowledge that we have at our disposal.

If you want to Learn Tai Chi but are worried about your knees, consider learning a version like the Cheng Man-ch'ing version that promotes safe practices and upright postures.

Protect Your Knees with These 5 Steps

Select a style or form that does not place emphasis on very low postures. Cheng Man Ch’ing style offers this, as does the variations, specifically Dr Chi’s very upright version or William Chens. Avoid deep knee bends and dramatic postures - these are for WuShu exhibitions - not for your health.

The ligaments support the hinge function of the knee (moving forward and back). Forcing the knee ligaments to adopt a twisting motion, weakens them, not strengthens them. So adapt any knee rotational movements. Especially when bearing weight on the leg. Do not be afraid to vary the form from what your instructor teaches. Tai Chi is either an evolutionary art or a stagnant art. You decide.

Improve your posture by building strength in the quads, the calves and the hamstrings to help strengthen the Knee joint and help hold it in place.

Remember that it’s the role of the hips to rotate, not the knees. Work on opening the hips and improving their ability, whilst stabilising the knees (and keeping them soft - or open)

Watch the webinar on Knees and the follow up webinar on balance (found on the teapotmonk 21st century training site).

More Information on REPORT

-

Lack of Standardisation in American Taijiquan Instruction

The sources provide compelling evidence to support the argument that Taijiquan instruction in America is not standardised. This lack of uniformity is evident in various aspects, including:

Diverse Definitions and Interpretations: Dunbar's dissertation [1] highlights the wide array of definitions and interpretations of Taijiquan among American instructors. He identifies six thematic categories within those definitions - Energic, Relaxational, Mentative, Healthful, Martial, and Unitive - indicating a lack of consensus on the core essence and purpose of Taijiquan. [2-4] While 48% of surveyed instructors acknowledged the martial aspect, a significant number downplayed or even disregarded it, further demonstrating the lack of a unified understanding. [5] This diversity in understanding and presentation contributes significantly to the non-standardised nature of Taijiquan instruction in America.

Varied Teaching Methodologies: The absence of a standardised instructional approach is apparent in the range of teaching methodologies employed by American instructors. Dunbar's research identifies a spectrum, from traditional "watch and copy" methods to more contemporary approaches incorporating modern understandings of physiology, biomechanics, and effective pedagogy. [6, 7] This variation in teaching styles, as noted in our conversation, creates a situation where the learning experience can differ significantly depending on the instructor a student chooses. [8]

Discrepancies in Teacher Training and Qualifications: The sources also reveal a lack of standardisation in teacher training and qualifications. While 92% of surveyed instructors believed that Taijiquan must be learned from a qualified teacher, there were no established criteria for what constitutes "qualified." [9] The absence of a formal certification process, as highlighted in the dissertation, allows individuals with varying levels of experience, training, and even understanding of Taijiquan to present themselves as instructors. [10] Dunbar found this lack of regulation concerning, as it can lead to the perpetuation of misinformation, ineffective teaching practices, and even potential harm to students. [11]

The lack of standardisation in American Taijiquan instruction creates a complex and multifaceted landscape. While this allows for flexibility and individualised learning experiences, it also poses challenges, particularly for newcomers navigating this diverse world. The absence of universally accepted standards makes it challenging to ensure quality control and may lead to inconsistent learning outcomes.

-

Critique of "100 Flowers Bloom copy - flattened.pdf"

The provided excerpt from J.Y. Dunbar's 1991 dissertation, "Let a Hundred Flowers Bloom! A Profile of Taijiquan Instruction in America," offers a rich exploration of the state of Taijiquan instruction in America at the time. Here's a critique of the excerpt, highlighting its strengths and limitations:

Strengths:

Comprehensive Scope: Dunbar's dissertation, even in excerpt, attempts to capture the multifaceted nature of Taijiquan instruction in America. It goes beyond a simple "how-to" guide and examines the philosophical underpinnings, teaching methodologies, perceived health benefits, and the challenges of standardisation within the field. The inclusion of diverse voices and perspectives enriches the study, reflecting the dynamism and evolving nature of this practice in a Western context.

Focus on Teacher Perspectives: A significant strength of Dunbar's work is its emphasis on the perspectives of Taijiquan instructors. By analysing their definitions of the art, preferred teaching methods, and concerns, the dissertation provides valuable insights into the beliefs and practices shaping Taijiquan instruction across America. This approach illuminates the diversity of thought and the lack of a singular, unified approach, a point often overlooked in research.

Identification of Key Issues: The excerpt effectively identifies several key issues and tensions within the American Taijiquan community, such as the downplaying of the martial aspect, the lack of standardised teacher training and qualifications, and the need for a more balanced approach that blends tradition with contemporary understandings of the body and effective pedagogy.

Inductive Approach and Taxonomy Development: The excerpt demonstrates a commendable inductive approach to data analysis. Dunbar meticulously analyses qualitative responses, deriving thematic categories for defining Taijiquan and developing a taxonomy of effective teaching strategies. This grounded approach adds rigour and depth to his findings.

Call for Balanced Approach and Continued Learning: A significant contribution of Dunbar's work is its call for a more balanced and informed approach to Taijiquan instruction. He advocates for integrating traditional wisdom with modern knowledge, encouraging instructors to deepen their understanding of physiology, biomechanics, and effective teaching methodologies.

Limitations:

Limited Generalisability: The study was conducted in 1988, and the field of Taijiquan has likely evolved since then. Additionally, the survey respondents, while numerous, might not fully represent the entirety of Taijiquan instructors in America across different regions, lineages, or styles. Therefore, while the findings offer valuable historical insights, their generalisability to contemporary Taijiquan instruction might be limited.

Potential for Subjectivity in Qualitative Analysis: While Dunbar's inductive analysis of qualitative data is a strength, it's important to acknowledge the potential for subjectivity inherent in such an approach. Different researchers might interpret the same data differently, leading to varying conclusions.

Lack of Specific Recommendations: While the excerpt identifies critical areas for improvement, like the need for standardisation and a more scientifically informed approach, it offers limited concrete recommendations for addressing these challenges.

Absence of Cross-Cultural Comparison: The excerpt primarily focuses on the American context, which is a limitation, as acknowledging and learning from Taijiquan instruction in other cultural contexts (like the UK, as you mentioned) could provide valuable insights and broaden the understanding of the art's global evolution.

Overall, J.Y. Dunbar's dissertation excerpt provides a valuable snapshot of Taijiquan instruction in America in the late 1980s. Its comprehensive scope, teacher-centric approach, and identification of key issues make it a significant contribution to the field. However, its limitations, particularly the limited generalisability of its findings and the lack of concrete recommendations, should be considered.

WHAT ELSE YOU CAN DO?

If you are working with me on any of my Online Courses, then make sure you join the Academy - its free to do so and you will get more health related reports and videos posted each month.

*Tai Chi teachers Survey: J. Dunbar 1991. Let a 1000 Flowers Bloom